Just how secure is Tor, one of the most widely used internet privacy tools? Court documents released from the Silk Road 2.0 trial suggest that a “university-based research institute” provided information that broke Tor’s privacy protections, helping identify the operator of the illicit online marketplace.

Silk Road and its successor Silk Road 2.0 were run as a Tor hidden service, an anonymised website accessible only over the Tor network which protects the identity of those running the site and those using it. The same technology is used to protect the privacy of visitors to other websites including journalists reporting on mafia activity, search engines and social networks, so the security of Tor is of critical importance to many.

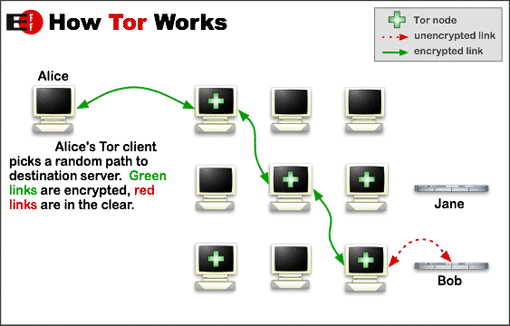

How Tor’s privacy shield works

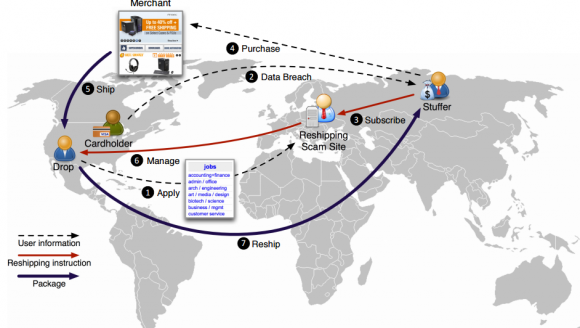

Almost 97% of Tor traffic is from those using Tor to anonymise their use of standard websites outside the network. To do so a path is created through the Tor network via three computers (nodes) selected at random: a first node entering the network, a middle node (or nodes), and a final node from which the communication exits the Tor network and passes to the destination website. The first node knows the user’s address, the last node knows the site being accessed, but no node knows both.

The remaining 3% of Tor traffic is to hidden services. These websites use “.onion” addresses stored in a hidden service directory. The user first requests information on how to contact the hidden service website, then both the user and the website make the three-hop path through the Tor network to a rendezvous point which joins the two connections and allows both parties to communicate.

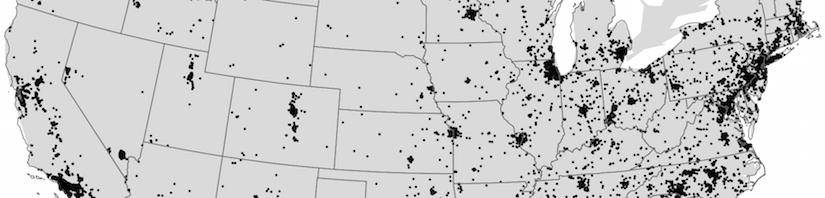

In both cases, if a malicious operator simultaneously controls both the first and last nodes to the Tor network then it is possible to link the incoming and outgoing traffic and potentially identify the user. To prevent this, the Tor network is designed from the outset to have sufficient diversity in terms of who runs nodes and where they are located – and the way that nodes are selected will avoid choosing closely related nodes, so as to reduce the likelihood of a user’s privacy being compromised.

This type of design is known as distributed trust: compromising any single computer should not be enough to break the security the system offers (although compromising a large proportion of the network is still a problem). Distributed trust systems protect not only the users, but also the operators; because the operators cannot break the users’ anonymity – they do not have the “keys” themselves – they are less likely to be targeted by attackers.

Unpeeling the onion skin

With about 2m daily users Tor is by far the most widely used privacy system and is considered one of the most secure, so research that demonstrates the existence of a vulnerability is important. Most research examines how to increase the likelihood of an attacker controlling both the first and last node in a connection, or how to link incoming traffic to outgoing.

When the 2014 programme for the annual BlackHat conference was announced, it included a talk by a team of researchers from CERT, a Carnegie Mellon University research institute, claiming to have found a means to compromise Tor. But the talk was cancelled and, unusually, the researchers did not give advance notice of the vulnerability to the Tor Project in order for them to examine and fix it where necessary.

This decision was particularly strange given that CERT is worldwide coordinator for ensuring software vendors are notified of vulnerabilities in their products so they can fix them before criminals can exploit them. However, the CERT researchers gave enough hints that Tor developers were able to investigate what had happened. When they examined the network they found someone was indeed attacking Tor users using a technique that matched CERT’s description.

The multiple node attack

The attack turned on a means to tamper with a user’s traffic as they looked up the .onion address in the hidden service directory, or in the hidden service’s traffic as it uploaded the information to the directory.

Continue reading How Tor’s privacy was (momentarily) broken, and the questions it raises

As a child,

As a child,