Paying for dinner? A taxi ride? A tropical drink? Sure. Swipe or tap your card and it is done. Convenient. Payment cards make it easy for us to make payments at “brick-and-mortar” locations and online marketplaces. However, they are also attractive targets for cybercriminals seeking to steal funds from the accounts linked to payment cards, as seen in this recent high-profile theft of credit cards affecting more than 1,000 hotels, for instance.

Theft of payment card information via phishing, skimming, or hacking, is usually the first step in the chain of payment card fraud. Other steps include sales, validation, and monetisation of the stolen data. These illicit deals are aided by underground online forums where cybercriminals actively trade stolen credit card information. To tackle payment card fraud, it is therefore important to understand the characteristics of these forums and the activity of miscreants using them. In our paper, presented at the 2017 APWG Symposium on Electronic Crime Research (eCrime2017), we analyse and discuss the characteristics of underground carding forums. We focus on the available products and prices, characteristics of sellers, and features of the forums. We won the Best Paper Award at eCrime2017.

Products

The main products available on carding forums are credit card numbers, dumps, and fullz. Credit card numbers comprise the information actually printed on credit cards, that is, cardholder name, card number (16 digits on most cards), expiry date, and the security code on the back of the card (usually 3 digits).

Dumps comprise stolen information from the tracks of magnetic stripe of a credit card. Dumps are usually obtained via skimmers. Skimmers are devices attached to Automated Teller Machines (ATMs) and Point of Sale (POS) terminals by miscreants to steal data from unsuspecting victims. Afterwards, the miscreants create clones of the skimmed credit cards and monetise the clones, for instance, by making illicit purchases with them.

Fullz contain further information about the cardholder. In other words, fullz usually comprise information printed on the card plus additional information such as bank account information, cardholder’s date of birth, Social Security number, etc.

Sellers

Generally, there are several types of participants on carding forums: sellers, buyers, intermediaries, mules, administrators, and others. These roles are not mutually exclusive; sellers may simultaneously be buyers. In this study, we focus on sellers since they come before buyers in the fraud chain.

Our approach

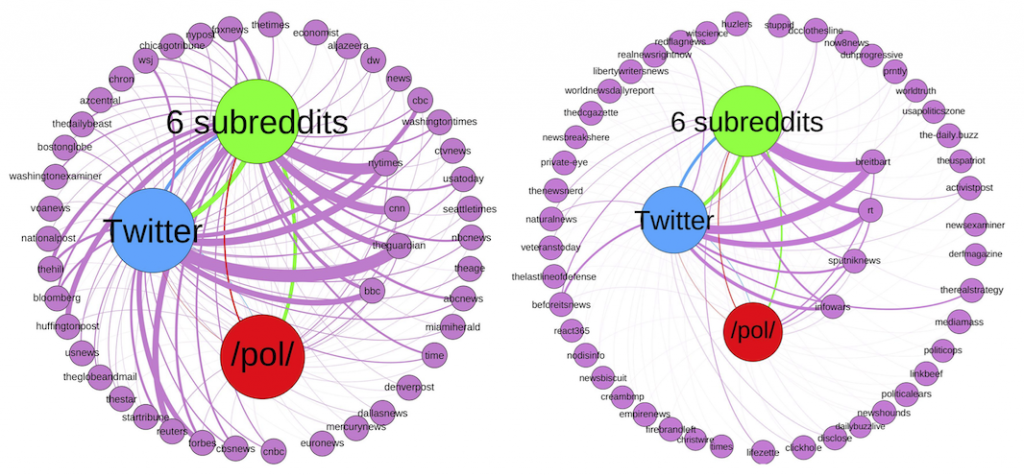

We studied previous work on underground marketplaces and forums, and derived the following hypotheses from the insights gained. We then searched for names of carding forums, found 25 names, and collected data from 5 active forums. We then tested the hypotheses on the data.

Hypothesis 1. Prices of fullz (credit card numbers and additional cardholder information) are higher than prices of credit card numbers.

Hypothesis 2. A small number of traders are responsible for a large

proportion of traffic.

Hypothesis 3. Most traders sell only one product type (that is, they are specialised).

Hypothesis 4. Specialised traders sell their products at lower prices than unspecialised traders.

Hypothesis 5. Carding forums have working reputation systems that are as sophisticated as those of legal marketplaces (for instance, eBay).

Hypothesis 6. The vast majority of actors do not operate on more than

one forum.

Summary of findings

Our analyses confirmed Hypothesis 1, Hypothesis 2, and Hypothesis 6. In other words, prices of fullz are indeed higher than prices of credit card numbers (credit card numbers: mean = $10.08, median = $10.00; fullz: mean = $31.82, median = $30.00). Also, a small number of traders are responsible for a large proportion of traffic. Finally, most sellers focus their efforts on a single forum, as expected.

Hypothesis 4 was partially rejected, while Hypothesis 3 and Hypothesis 5 were completely rejected. In other words, specialised sellers do not always sell their products at lower prices than the unspecialised ones, most sellers advertise more than one type of product, and most of the carding forums under study do not have working reputation systems that are as elaborate as those of legitimate online marketplaces.

In conclusion, dumps and fullz are relatively expensive; they are more than three times as expensive as credit card numbers. This may be due to the effort needed to obtain or monetise the data, the amount of available information, or differing supply and demand. Sellers have varying success. Even though some sellers complete hundreds of transactions, most sellers do not succeed in selling anything. This means that the trading sections of the forums are profitable distribution channels for high-profile actors. Finally, specialisation is not a key characteristic of sellers, not even of high-profile sellers.

Further details can be found in the full paper All Your Cards Are Belong To Us: Understanding Online Carding Forums, by Andreas Haslebacher, Jeremiah Onaolapo, and Gianluca Stringhini.