The MIKEY-SAKKE protocol is being promoted by the UK government as a better way to secure phone calls. The reality is that MIKEY-SAKKE is designed to offer minimal security while allowing undetectable mass surveillance, through the introduction a backdoor based around mandatory key-escrow. This weakness has implications which go further than just the security of phone calls.

The current state of security for phone calls leaves a lot to be desired. Land-line calls are almost entirely unencrypted, and cellphone calls are also unencrypted except for the radio link between the handset and the phone network. While the latest cryptography standards for cellphones (3G and 4G) are reasonably strong it is possible to force a phone to fall back to older standards with easy-to-break cryptography, if any. The vast majority of phones will not reveal to their user whether such an attack is under way.

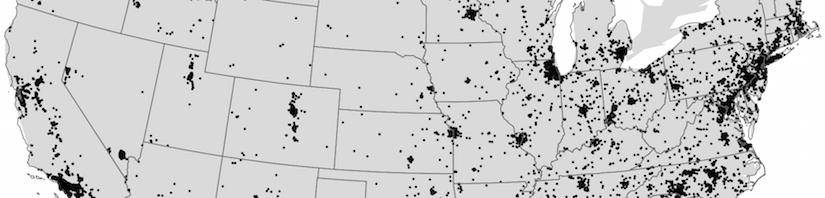

The only reason that eavesdropping on land-line calls is not commonplace is that getting access to the closed phone networks is not as easy compared to the more open Internet, and cellphone cryptography designers relied on the equipment necessary to intercept the radio link being only affordable by well-funded government intelligence agencies, and not by criminals or for corporate espionage. That might have been true in the past but it certainly no longer the case with the necessary equipment now available for $1,500. Governments, companies and individuals are increasingly looking for better security.

A second driver for better phone call encryption is the convergence of Internet and phone networks. The LTE (Long-Term Evolution) 4G cellphone standard – under development by the 3rd Generation Partnership Project (3GPP) – carries voice calls over IP packets, and desktop phones in companies are increasingly carrying voice over IP (VoIP) too. Because voice calls may travel over the Internet, whatever security was offered by the closed phone networks is gone and so other security mechanisms are needed.

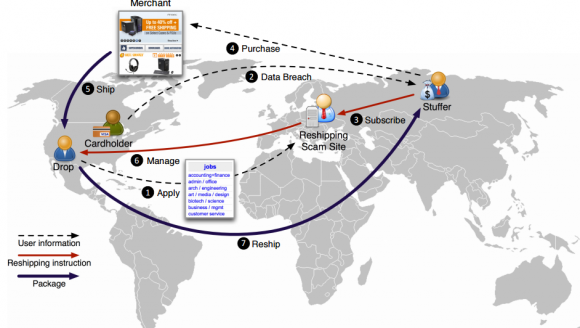

Like Internet data encryption, voice encryption can broadly be categorised as either link encryption, where each intermediary may encrypt data before passing it onto the next, or end-to-end encryption, where communications are encrypted such that only the legitimate end-points can have access to the unencrypted communication. End-to-end encryption is preferable for security because it avoids intermediaries being able to eavesdrop on communications and gives the end-points assurance that communications will indeed be encrypted all the way to their other communication partner.

Current cellphone encryption standards are link encryption: the phone encrypts calls between it and the phone network using cryptographic keys stored on the Subscriber Identity Module (SIM). Within the phone network, encryption may also be present but the network provider still has access to unencrypted data, so even ignoring the vulnerability to fall-back attacks on the radio link, the network providers and their suppliers are weak points that are tempting for attackers to compromise. Recent examples of such attacks include the compromise of the phone networks of Vodafone in Greece (2004) and Belgacom in Belgium (2012), and the SIM card supplier Gemalto in France (2010). The identity of the Vodafone Greece hacker remains unknown (though the NSA is suspected) but the attacks against Belgacom and Gemalto were carried out by the UK signals intelligence agency – GCHQ – and only publicly revealed from the Snowden leaks, so it is quite possible there are others attacks which remain hidden.

Email is typically only secured by link encryption, if at all, with HTTPS encrypting access to most webmail and Transport Layer Security (TLS) sometimes encrypting other communication protocols that carry email (SMTP, IMAP and POP). Again, the fact that intermediaries have access to plaintext creates a vulnerability, as demonstrated by the 2009 hack of Google’s Gmail likely originating from China. End-to-end email encryption is possible using the OpenPGP or S/MIME protocols but their use is not common, primarily due to their poor usability, which in turn is at least partially a result of having to stay compatible with older insecure email standards.

In contrast, instant messaging applications had more opportunity to start with a clean-slate (because there is no expectation of compatibility among different networks) and so this is where much innovation in terms of end-to-end security has taken place. Secure voice communication however has had less attention than instant messaging so in the remainder of the article we shall examine what should be expected of a secure voice communication system, and in particular see how one of the latest and up-coming protocols, MIKEY-SAKKE, which comes with UK government backing, meets these criteria.

MIKEY-SAKKE and Secure Chorus

MIKEY-SAKKE is the security protocol behind the Secure Chorus voice (and also video) encryption standard, commissioned and designed by GCHQ through their information security arm, CESG. GCHQ have announced that they will only certify voice encryption products through their Commercial Product Assurance (CPA) security evaluation scheme if the product implements MIKEY-SAKKE and Secure Chorus. As a result, MIKEY-SAKKE has a monopoly over the vast majority of classified UK government voice communication and so companies developing secure voice communication systems must implement it in order to gain access to this market. GCHQ can also set requirements of what products are used in the public sector and as well as for companies operating critical national infrastructure.

UK government standards are also influential in guiding purchase decisions outside of government and we are already seeing MIKEY-SAKKE marketed commercially as “government-grade security” and capitalising on their approval for use in the UK government. For this reason, and also because GCHQ have provided implementers a free open source library to make it easier and cheaper to deploy Secure Chorus, we can expect wide use MIKEY-SAKKE in industry and possibly among the public. It is therefore important to consider whether MIKEY-SAKKE is appropriate for wide-scale use. For the reasons outlined in the remainder of this article, the answer is no – MIKEY-SAKKE is designed to offer minimal security while allowing undetectable mass surveillance though key-escrow, not to provide effective security.

Continue reading Insecure by design: protocols for encrypted phone calls