In this post, we reflect on the current state of cybersecurity and the fight against cybercrime, and identify, we believe, one of the most significant drawbacks Information Security is facing. We argue that what is needed is a new, complementary research direction towards improving systems security and cybercrime mitigation, which combines the technical knowledge and insights gained from Information Security with the theoretical models and systematic frameworks from Environmental Criminology. For the full details, you can read our paper – “Bridging Information Security and Environmental Criminology Research to Better Mitigate Cybercrime.”

The fight against cybercrime is a long and arduous one. Not a day goes by without us hearing (at an increasingly alarming rate) the latest flurry of cyber attacks, malware operations, (not so) newly discovered vulnerabilities being exploited, and the odd sprinkling of a high-profile victim or a widely-used service being compromised by cybercriminals.

A burden borne for too long?

Today, the topic of security and cybercrime is one that is prominent in a number of circles and fields of research (e.g., crime science and criminology, law, sociology, economics, policy, policing), not to talk of wider society. However, for the best part of the last half-century, the burden of understanding and mitigating cybercrime, and improving systems security has been predominantly borne by information security researchers and computer engineers. Of course, this is entirely reasonable. As circumstances had long dictated, the exponential penetration and growth in the capability of digital technologies co-dependently brought the opportunity for malicious exploitation, and, alongside it, the need to combat and prevent such malicious activities. Enter the arms race.

However, and potentially the biggest downside to holding this solitary responsibility for so long, the traditional, InfoSec approach to security and cybercrime prevention has leaned heavily towards the technical side of this mantle: discovering vulnerabilities, creating patches, redefining secure software design (e.g., STRIDE), conceptualising threat models for technical systems, and developing technologies to detect, prevent, and/or counter these threats. But, with the threat landscape of today, is this enough?

Taking stock

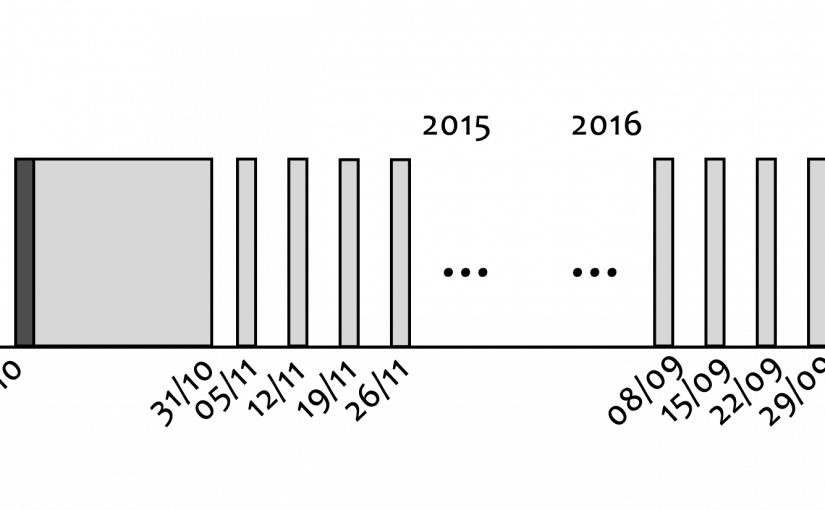

Make no mistake, it is clear that such technical skill-sets and innovations that abound and are produced from information security are invaluable in keeping up with similarly skilled and innovative cybercriminals. Unfortunately, however, one may find that such approaches to security and preventing cybercrime are generally applied in an ad hoc manner and lacking systemic structure, with, on the other hand, focus being constantly drawn towards the “top” vulnerabilities (e.g., OWASP’s Top 10) as opposed to “less important” ones (which are just as capable in enabling a compromise), or focus on the most recent wave of cyber threats as opposed to those only occurring a few years ago (e.g., the Mirai botnet and its variants, which have been active as far back as 2016, but are seemingly now on the back burner of priorities).

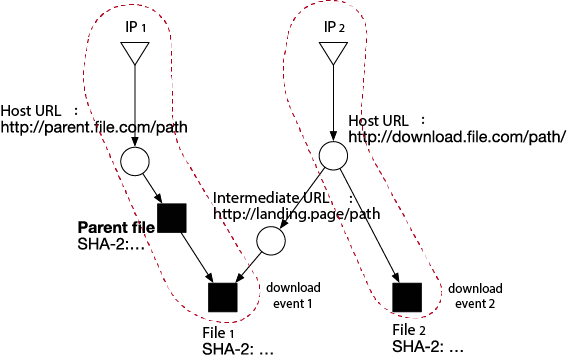

How much thought, can we say, is being directed towards understanding the operational aspects of cybercrime – the journey of the cybercriminal, so to speak, and their opportunity framework? Patching vulnerabilities and taking down botnets are indeed important, but how much attention is placed on understanding criminal displacement and adaptation: the shift of criminal activity from one form to another, or the adaptation of cybercriminals (and even the victims, targets, and other stakeholders), in reaction to new countermeasures? Are system designers taking the necessary steps to minimise the attack surfaces effectively, considering all techniques available to them? Is it enough to look a problem at face value, develop a state-of-the-art detection system, and move on to the next one? We believe much more can and should be done.

Continue reading We’re fighting the good fight, but are we making full use of the armoury?