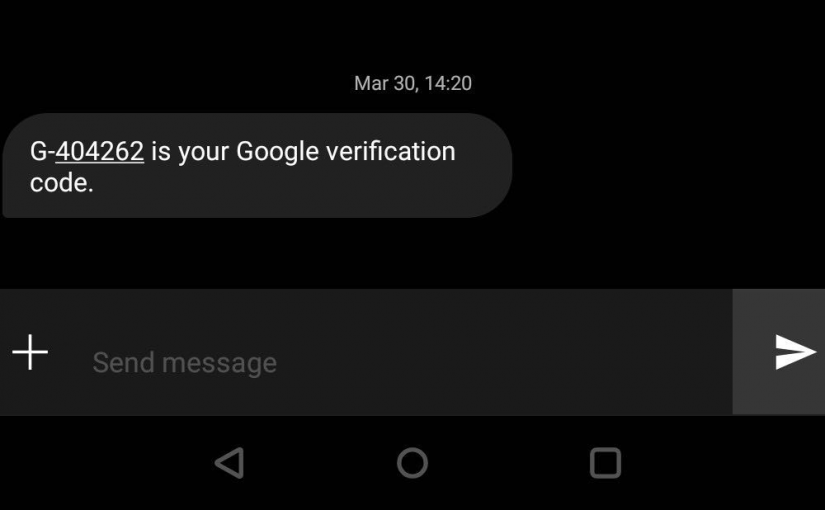

In October last year, analysts at Cyble published an article on the return of the Drinik malware that was first spotted by CERT-In in 2016. Last month during the tax-paying season of the year, I (Sharad Agarwal), a Ph.D. student at University College London (UCL) researching SMS phishing, found and identified an updated version of the Drinik malware that impersonates the Income Tax Department of India and targets the victim’s UPI (Unified Payment Interface) payment apps.

The iAssist.apk malware was being spread from the URL hxxp://198[.]46[.]177[.]176/IT-R/?id={mobile number} where the user is deceived into downloading a new version of the app, impersonating the Income Tax Department of India. Along with Daniel Arp, I analyzed the malware sample to check for new functionalities compared to previous versions. In the following, we give a brief overview of our findings.

Communication

Our analysis found that the malware communicates with the Command & Control (C&C) server hxxp://msr[.]servehttp[.]com, which is hosted on IP 107[.]174[.]45[.]116. It also silently drops another malicious APK file hosted on the C&C to the victim’s mobile that has already been identified and flagged as malware on VirusTotal – “GAnalytics.apk“.

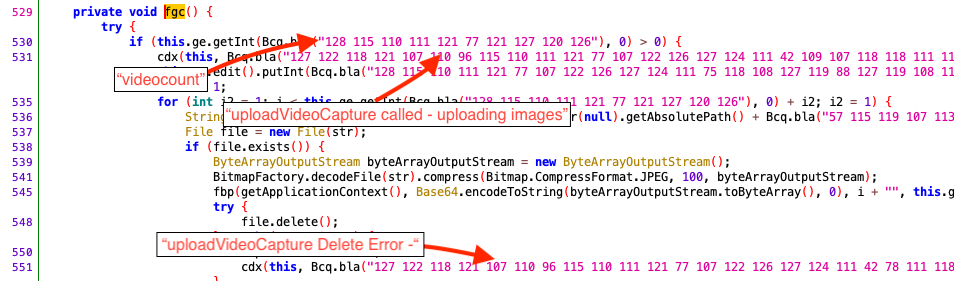

The previous campaign used a different IP for its C&C communication. However, the hosting provider for the IP addresses, “ColoCrossing“, is the same as in the previous campaign. This strongly indicates that the Threat Actor behind both campaigns is also the same and is abusing the same hosting provider again. As has already been reported for previous versions of this malware, also the most recent version of the malware records the screen of the mobile device and sends the recorded data to the C&C server (see Figure 1).

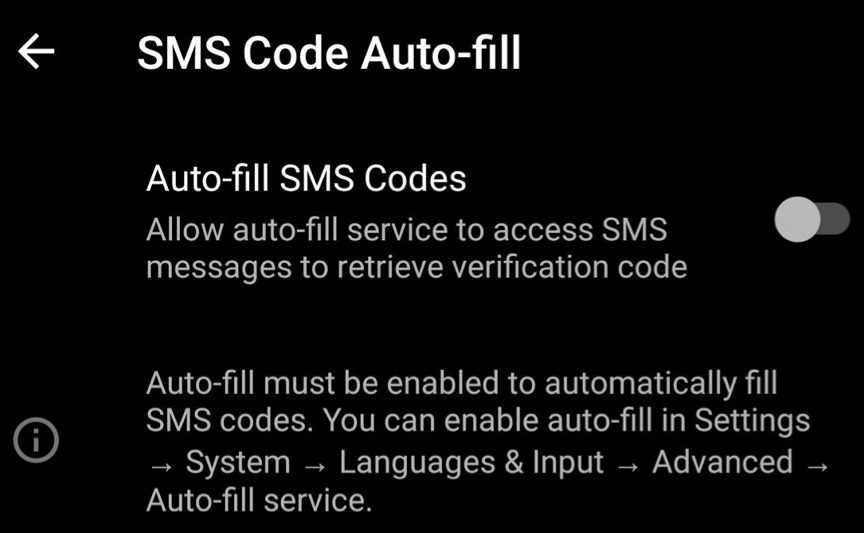

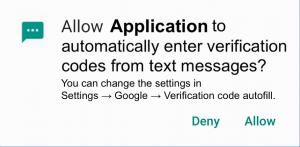

Additionally, we also found the phone numbers used by the criminals to which the SMSs are sent through this malware (see Table 1). The malicious APK asks for READ, WRITE, RECEIVE, and SEND SMS permission during the installation and does not work unless the user accepts all the permissions (see Table 2).

| Indicator Type | Indicators |

|---|---|

| MD5 | 02e0f25d4a715e970cb235f781c855de |

| SHA256 | 99422143d1c7c82af73f8fdfbf5a0ce4ff32f899014241be5616a804d2104ebf |

| C&C hostname | hxxp://msr[.]servehttp[.]com |

| C&C IP Address | 107[.]174[.]45[.]116 |

| Dropped APK URL | hxxp://107[.]174[.]45[.]116/a/GAnalytics[.]apk |

| Dropped APK MD5 | 95adedcdcb650e476bfc1ad76ba09ca1 |

| Dropped APK SHA256 | 095fde0070e8c1a10342ab0c1edbed659456947a2d4ee9a412f1cd1ff50eb797 |

| UPI Apps targetted | Paytm, Phonepe, and GooglePay |

| SMS sent to Phone numbers | +91-7829-806-961 (Vodafone), +91-7414-984-964 (Airtel, Jaora, Madhya Pradesh), and +91-9686-590-728 (Airtel, Karnataka) |

Continue reading Return of a new version of Drinik Android malware targeting Indian Taxpayers