Credit cards are a popular target for cybercriminals. Miscreants infect victim computers with malware that reports back to their command and control servers any credit card information that the user inserts in her computer, or compromise large retail stores stealing their customers’ credit card information. After obtaining credit card details from their victims, cybercriminals face the problem of monetising such information. As we recently covered on this blog, cybercriminals monetise stolen credit cards by cloning them and using very clever tricks to bypass the Chip and PIN verification mechanisms. This way they are able to use the counterfeit credit card in a physical store, purchase expensive items such as cigarettes, and re-sell them for a profit.

Another possible way for cybercriminals to monetise stolen credit cards is by purchasing goods on online stores. To this end, they need more information than the one contained on the credit card alone: for those of you who are familiar with online shopping, some merchants require a billing address as well to allow the purchase (which is called “card not present transaction”). This additional information is often available to the criminal – it might, for example, have been retrieved together with the credit card credentials as part of a data breach against an online retailer. When purchasing goods online, cybercriminals face the issue of shipping: if they shipped the stolen goods to their home address, this would make it easy for law enforcement to find and arrest them. For this reason, miscreants need intermediaries in the shipping process.

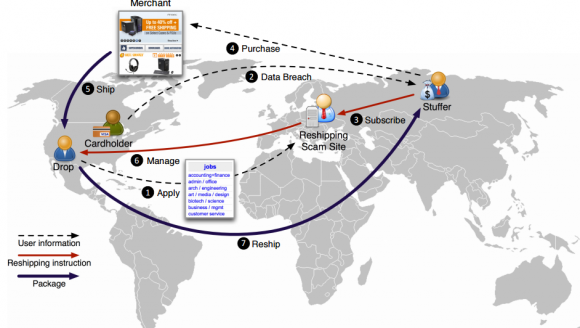

In our recent paper, which was presented at the ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security (CCS), we analyse a criminal scheme designed to help miscreants who wish to monetise stolen credit cards as we described: A cybercriminal (called operator) recruits unsuspecting citizens with the promise of a rewarding work-from-home job. This job involves receiving packages at home and having to re-ship them to a different address, provided by the operator. By accepting the job, people unknowingly become part of a criminal operation: the packages that they receive at their home contain stolen goods, and the shipping destinations are often overseas, typically in Russia. These shipping agents are commonly known as reshipping mules (or drops for stuff in the underground community). The operator then rents shipping mules as a service to cybercriminals wanting to ship stolen goods abroad. The cybercriminals taking advantage of such services are known as stuffers in the underground community. As a price for the service, the stuffer will pay a commission to the operator for each package reshipped through the service.

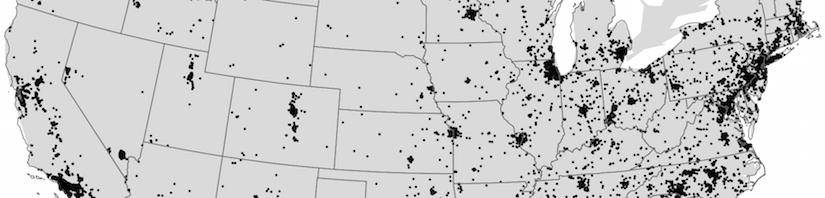

In collaboration with the FBI and the United States Postal Inspection Service (USPIS) we conducted a study on such reshipping scam sites. This study involved data coming from seven different reshipping sites, and provides the research community with invaluable insights on how these operations are run. We observed that the vast majority of the re-shipped packages end up in the Moscow, Russia area, and that the goods purchased with stolen credit cards span multiple categories, from expensive electronics such as Apple products, to designer clothes, to DSLR cameras and even weapon accessories. Given the amount of goods shipped by the reshipping mule sites that we analysed, the annual revenue generated from such operations can span between 1.8 and 7.3 million US dollars. The overall losses are much higher though: the online merchant loses an expensive item from its inventory and typically has to refund the owner of the stolen credit card. In addition, the rogue goods typically travel labeled as “second hand goods” and therefore custom taxes are also evaded. Once the items purchased with stolen credit cards reach their destination they will be sold on the black market by cybercriminals.

Studying the management of the mules lead us to some surprising findings. When applying for the job, people are usually required to send the operator copies of their ID cards and passport. After they are hired, mules are promised to be paid at the end of their first month of employment. However, from our data it is clear that mules are usually never paid. After their first month expires, they are never contacted back by the operator, who just moves on and hires new mules. In other words, the mules become victims of this scam themselves, by never seeing a penny. Moreover, because they sent copies of their documents to the criminals, mules can potentially become victims of identity theft.

Our study is the first one shedding some light on these monetisation schemes linked to credit card fraud. We believe the insights in this paper can provide law enforcement and researchers with a better understanding of the cybercriminal ecosystem and allow them to develop more effective mitigation techniques against these problems.

At the AARP Fraud Fighter Call Center, a division of AARP Fraud Watch Network, we speak with victim mules frequently, it is true that they don’t get paid. We warn them of identity theft and offer advice how to deal with the potential fallout from that.