In this post, we reflect on the current state of cybersecurity and the fight against cybercrime, and identify, we believe, one of the most significant drawbacks Information Security is facing. We argue that what is needed is a new, complementary research direction towards improving systems security and cybercrime mitigation, which combines the technical knowledge and insights gained from Information Security with the theoretical models and systematic frameworks from Environmental Criminology. For the full details, you can read our paper – “Bridging Information Security and Environmental Criminology Research to Better Mitigate Cybercrime.”

The fight against cybercrime is a long and arduous one. Not a day goes by without us hearing (at an increasingly alarming rate) the latest flurry of cyber attacks, malware operations, (not so) newly discovered vulnerabilities being exploited, and the odd sprinkling of a high-profile victim or a widely-used service being compromised by cybercriminals.

A burden borne for too long?

Today, the topic of security and cybercrime is one that is prominent in a number of circles and fields of research (e.g., crime science and criminology, law, sociology, economics, policy, policing), not to talk of wider society. However, for the best part of the last half-century, the burden of understanding and mitigating cybercrime, and improving systems security has been predominantly borne by information security researchers and computer engineers. Of course, this is entirely reasonable. As circumstances had long dictated, the exponential penetration and growth in the capability of digital technologies co-dependently brought the opportunity for malicious exploitation, and, alongside it, the need to combat and prevent such malicious activities. Enter the arms race.

However, and potentially the biggest downside to holding this solitary responsibility for so long, the traditional, InfoSec approach to security and cybercrime prevention has leaned heavily towards the technical side of this mantle: discovering vulnerabilities, creating patches, redefining secure software design (e.g., STRIDE), conceptualising threat models for technical systems, and developing technologies to detect, prevent, and/or counter these threats. But, with the threat landscape of today, is this enough?

Taking stock

Make no mistake, it is clear that such technical skill-sets and innovations that abound and are produced from information security are invaluable in keeping up with similarly skilled and innovative cybercriminals. Unfortunately, however, one may find that such approaches to security and preventing cybercrime are generally applied in an ad hoc manner and lacking systemic structure, with, on the other hand, focus being constantly drawn towards the “top” vulnerabilities (e.g., OWASP’s Top 10) as opposed to “less important” ones (which are just as capable in enabling a compromise), or focus on the most recent wave of cyber threats as opposed to those only occurring a few years ago (e.g., the Mirai botnet and its variants, which have been active as far back as 2016, but are seemingly now on the back burner of priorities).

How much thought, can we say, is being directed towards understanding the operational aspects of cybercrime – the journey of the cybercriminal, so to speak, and their opportunity framework? Patching vulnerabilities and taking down botnets are indeed important, but how much attention is placed on understanding criminal displacement and adaptation: the shift of criminal activity from one form to another, or the adaptation of cybercriminals (and even the victims, targets, and other stakeholders), in reaction to new countermeasures? Are system designers taking the necessary steps to minimise the attack surfaces effectively, considering all techniques available to them? Is it enough to look a problem at face value, develop a state-of-the-art detection system, and move on to the next one? We believe much more can and should be done.

In whatever direction you look, cybercriminals and their operations are showing themselves to become increasingly common, transatlantic, organised, opportunistic, and incredibly innovative. Perhaps most devastatingly, cybercriminals have beaten us to the punch in recognising the importance of multi-lateral thinking, organisation, and specialism: human vulnerabilities can be just as exploitable and effective as technical ones. Why “reinvent the wheel” when you can network with specialists and outsource parts of your operation to other cybercriminals and mules, or package and sell crimeware for others to use, simultaneously increasing economic efficiency and reducing one’s susceptibility to getting caught? Or, why not take advantage of legal and political discrepancies between different states that can support your criminal endeavours (jurisdictional arbitrage, anyone?), such as hosting core servers with “bulletproof” providers in politically unstable countries and poorly regulated regions. These are just some of the cybercriminal innovations that bypass the traditional “technical” dimension altogether.

Today, it is hard not to recognise that the technicality of security and cybercrime prevention is now only just one side of this complex and multi-faceted discussion.

It’s time for dialogue.

The interest in securing society from cyber-enabled and cyber-dependent threats and deviance is profound, and rightly so. Like technology, this interest penetrates all aspects of both the public and private sector, with very real implications for every member of society. Likewise, cybersecurity and preventing cybercrime are no longer challenges for information security alone but are now prominent focal points for other fields such as crime science, sociology, law, and policy, to name a few. The ubiquity and radical penetration of digital technologies in society, coupled with the increasingly complex interactions and mechanisms between hardware, software, and their users, has brought about variegated and constantly evolving opportunity structures for malfeasance, as exemplified by each new wave of cybercrime and customised cybercriminal operation that rears its head almost daily. Surely, therefore, the wise path to the end of controlling cybercrime and enhancing cybersecurity and online safety must entail a holistic approach, drawing value from a more extensive number of fields and perspectives that can help unravel these complexities and, ultimately, devise better solutions to account for them.

From a pragmatic view indeed, we believe that one field, in particular, can bring quick and significant returns if combined with the paradigms developed from information security: the field of environmental criminology.

Crime: forever the opportunist

Criminology, in general, is a broad and multidisciplinary subfield of sociology, drawing from the research of a range of social sciences, including sociology, psychology and social anthropology, as well as philosophy and biology. Classical criminology emphasises on the characteristics of offenders, and on the need to consider the distal factors (childhood development, current social, cultural, or economic conditions) that affect one’s propensity to engage in crime.

Environmental criminology is a unique subfield of criminology that, on the other hand, draws focus towards the immediate, environmental aspects of the crime event and establishing the situational context that enables a crime to occur. In essence, it moves away from the criminal and focuses on the crime. As such, environmental criminology draws on a wider range of technical fields, including geography, economics, and engineering, in order to assess the proximal (rather than the speculatively distal) aspects of the crime event that can explain why it occurred, and, thus, how it could be deterred. The rise of this field exemplifies a shift from the traditional thinking of crime only being committed by a “class” of society towards the idea that, to a larger degree, crime is generated by the opportunity to commit it. On a side note, this better explains why any member of society, under certain circumstances, may commit a criminal act, from fighting in bars, to exceeding speed limits, to soliciting illegal products or services.

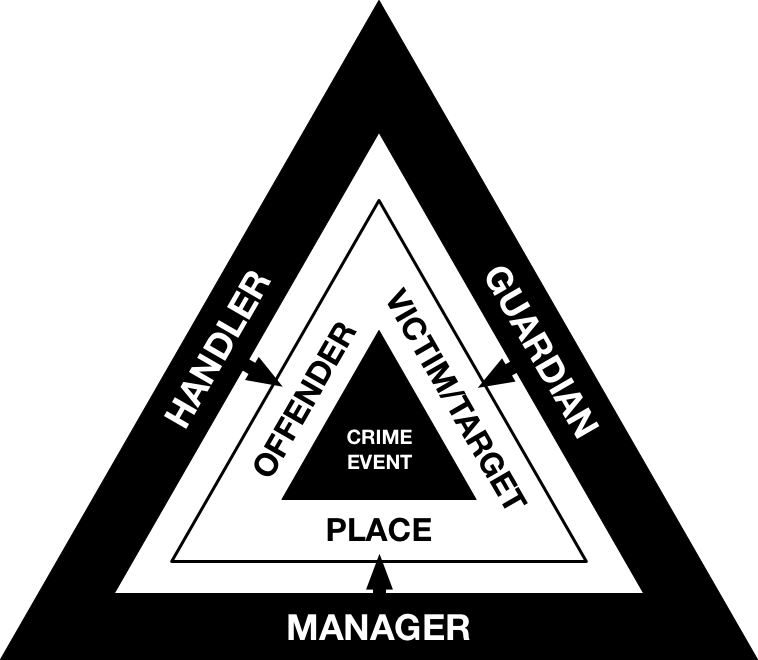

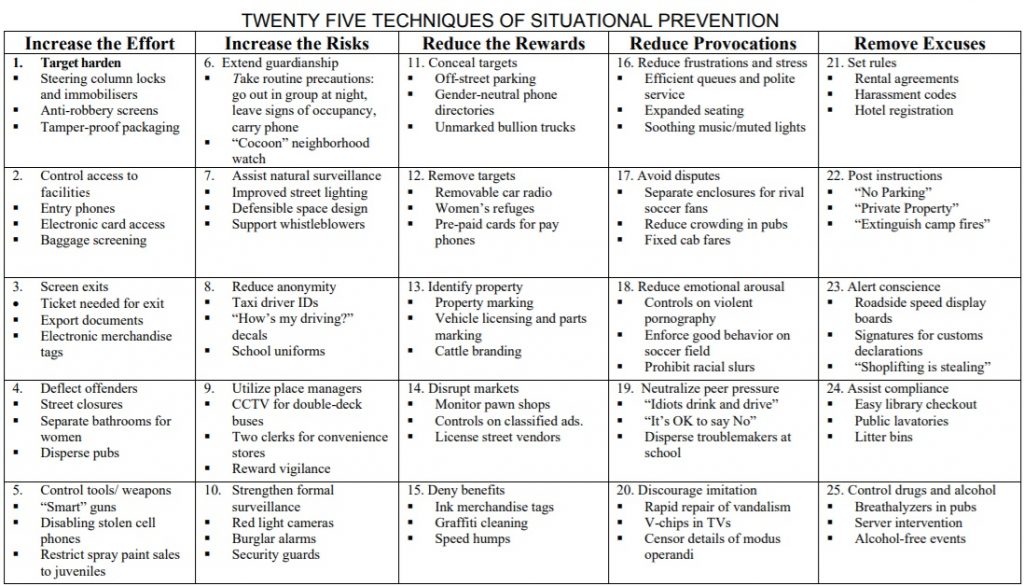

There are several important theories and concepts within environmental criminology (which we summarise in our paper), but a fundamental notion behind it is that predatory crime occurs when a motivated offender meets a suitable target or victim in time and space, and in the absence of a capable guardian. This interaction is otherwise known as the ‘crime triangle’ from Routine Activity Theory. As such, the key idea to prevent crime is to alter the environment (or design products) that reduce criminal opportunity, either with respect to discouraging the offender, protecting or removing the target or victim, or ensuring the presence of capable guardianship. Situational crime prevention provides a framework for reducing criminal opportunity in a crime event.

There is a wide range of successful case studies associated with environmental criminology, ranging from reductions in urban crime to mitigating acts of terrorism. As with any school of thinking, a number of criticisms have also been raised against it, such as its apparent focus on the “low-hanging fruit” of crime while ignoring root causes (Wortley and Tilley’s “Theories for Situational and Environmental Crime Prevention” provide a nice summary of these criticisms, as well as counter-arguments to them).

Bridging the gap

Since the turn of the millenium, environmental criminology has faced a shift in focus towards cybercrime. At the same time, researchers have begun to recognise a multitude of similarities and parallels between the contexts surrounding crime in the real-world versus crime in cyberspace (or cybercrime), as well as underlying similarities in the techniques used to prevent them. Such parallels, for example, include the crime triangle also being applicable to crimes in cyberspace (e.g., the interaction of online deviants with their victims, drive-by downloads occurring once compromised web content is accessed), cybercriminals and malware exhibiting similar behaviours to real-world criminals, showing some form of rationality (e.g., scanning for targets, evading detection), and security practitioners (unknowingly) exhibiting a similar insight and use of concepts and techniques from environmental criminology (e.g., early “engineer-criminologists” designing timesharing systems geared towards preventing misuse, agnostic to who may commit them).

Environmental criminology, like information security, is a field that is problem-oriented at heart and one that was born out of necessity. As such, its paradigms are constantly refined and adapted towards mitigating real crimes, with an added emphasis on applying the scientific method to evaluate the effects of interventions over time so as to deal with reactive mechanisms such as criminal displacement and adaptation. After surveying cybercrime literature from both fields and explicitly drawing out links between them, we have found that there is a common ideology between the two, which is their demonstrated by their focus on the contextual factors (or vulnerabilities), rather than the perpetrators themselves, that enable misuse and a proactive approach to mitigating cybercrime.

And, with this camaraderie comes opportunity.

As some have suggested before us, we propose that security researchers can benefit from the ideas of environmental criminology through implementing a synergistic approach. In particular, we recognise that, though there are already clear parallels between the theoretical models of environmental criminology and the mitigations devised by information security, security researchers are yet to fully explore the structured analytical and actionable processes that environmental criminology has to offer.

In particular, past and current mitigations devised by security researchers only seem to represent a subset of the full range of techniques that could be utilised, while lacking a systematic approach to establishing them. Also, it appears that little attention is directed towards the consideration, monitoring, and evaluation of the actual effects of mitigations, both with regards to the system (targets, victims, stakeholders) and the malicious actors themselves, and how they respond to these interventions.

However, by considering the fulness of the crime prevention process, environmental criminology can aid the design of systems and mitigations that are more likely to remain effective in both the short- and long-term. For example, designers of complex socio-technical systems can use such techniques and systematic processes to identify and mitigate risks (technical, human, etc.), while avoiding lapses in the security design process. From an offensive perspective, environmental criminology can better inform researchers on the most appropriate aspects of a cybercriminal operation to target in order to disrupt it (e.g., identifying crime hot spots in cyberspace, establishing “crime scripts” for the cybercrime in question, devising and weighing mitigations with their potential effects for each step of the criminal operation).

Of course, there is still some way to go in the task of bridging the conceptual frameworks between the two fields. Principally, there are valid arguments that contradict the applicability of environmental criminology, a field primarily based on concepts and crimes in the real world, towards mitigating crimes in cyberspace, a significantly different realm. As such, these key concepts need to be handled carefully when considering the context of cyberspace and cybercrime (in our paper, we assess these concepts, and introduce the concept of ‘cyberplace,’ which is analogous to the key concept of ‘place’). Furthermore, as already mentioned, the field of environmental criminology itself has its own criticisms that are yet under dispute, particularly by other criminologists.

Nonetheless, given the plethora of evidence available on the diversity and depths of its success in the real world, it would be folly for the security community not to further explore its potential in aiding the fight against cybercrime.

Time to revisit the armoury.

Special thanks go to my co-authors of our paper, Toby Davies, Steven J. Murdoch, and Gianluca Stringhini. Photo by Nik Shuliahin from Unsplash.