The French cybercrime unit, C3N, along with the FBI and Avast, recently took down the Retadup botnet that infected more than 850,000 computers, mostly in South America. Though this takedown operation was successful, the botnet was created as early as 2016, with the operators reportedly making millions of euros since. It is clear that large-scale analysis, monitoring, and detection of malicious downloads and botnet activity, even as far back as 2016, is still highly relevant today in the ongoing battle against increasingly sophisticated cybercriminals.

Malware delivery has undergone an impressive evolution since its inception in the 1980s, moving from being an amateur endeavor to a well-oiled criminal business. Delivery methods have evolved from the human-centric transfer of physical media (e.g., floppy disks), sending of malicious emails, and social engineering, to the automated delivery mechanisms of drive-by downloads (malicious code execution on websites and web advertisements), packaged exploit kits (software packages that fingerprint user browsers for specific exploits to maximise the coverage of potential victims), and pay-per-install (PPI) schemes (botnets that are rented out to other cybercriminals).

Furthermore, in recent times, researchers have uncovered the parallel economy of potentially unwanted programs (PUP), which share many traits with the malware ecosystem (such as their delivery through social engineering and PPI networks), while being primarily controlled by different actors. However with some types of PUP, including adware and spyware, PUP has generally been regarded as an annoyance rather than a direct threat to security.

Using the download metadata of millions of users worldwide from 2015/16, we (Colin C. Ife, Yun Shen, Steven J. Murdoch, Gianluca Stringhini) carried out a comprehensive measurement study in the short-term (a 24-hour period), the medium-term (daily, over the course of a month), and the long-term (weekly, over the course of a year) to characterise the structure of this complex malicious file delivery ecosystem on the Web, and how it evolves over time. This work provides us with answers to some key questions, while, at the same time, posing some more and exemplifying some significant issues that continue to hinder security research on unwanted software activity.

An Overview

There were three main research questions that influenced this study, which we will traverse in the following sections of this post:

-

- What does the malicious file delivery ecosystem look like?

- How do the networks that deliver only malware, only PUP, or both compare in structure?

- How do these file delivery infrastructures and their activities change over time?

For full technical details, you can refer to our paper – Waves of Malice: A Longitudinal Measurement of the Malicious File Delivery Ecosystem on the Web – published by and presented at the ACM AsiaCCS 2019 conference.

The Data

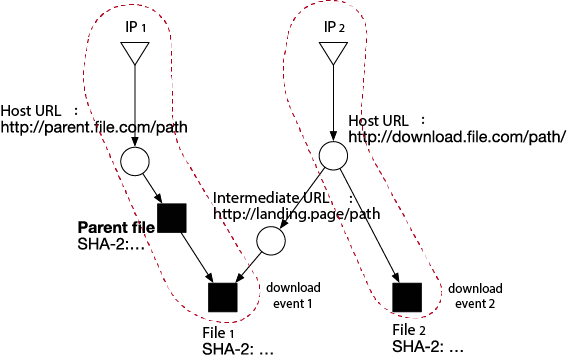

The dataset was provided (and pre-sanitized) by Symantec and consisted of 129 million download events generated by 12 million users. Each download event contained information such as the timestamp, the SHA-2s of the downloaded file and its parent file, the filename, the size (in bytes), the referrer URL, Host URLs (landing pages after redirection) of the download and parent file, and the IP address hosting the download.