This week, the Wall Street Journal published an article by Robert McMillan containing an apology from Bill Burr, a man whose name is unknown to most but whose work has caused daily frustration and wasted time for probably hundreds of millions of people for nearly 15 years. Burr is the author of the 2003 Special Publication 800-63. Appendix A from the US National Institute of Standards and Technology: eight pages that advised security administrators to require complex passwords including special characters, capital letters, and numbers, and dictate that they should be frequently changed.

“Much of what I did I now regret,” Burr told the Journal. In June, when NIST issued a completely rewritten document, it largely followed the same lines as the NCSCs password guidance, published in 2015 and based on prior research and collaboration with the UK Research Institute in Science of Cyber Security (RISCS), led from UCL by Professor Angela Sasse. Yet even in 2003 there was evidence that Burr’s approach was the wrong one: in 1999, Sasse did the first work pointing out the user-unfriendliness of standard password policies in the paper Users Are Not the Enemy, written with Anne Adams.

How much did that error cost in lost productivity and user frustration? Why did it take the security industry and research community 15 years to listen to users and admit that the password policies they were pushing were not only wrong but actively harmful, inflicting pain on millions of users and costing organisations huge sums in lost productivity and administration? How many other badly designed security measures are still out there, the cyber equivalent of traffic congestion and causing the same scale of damage?

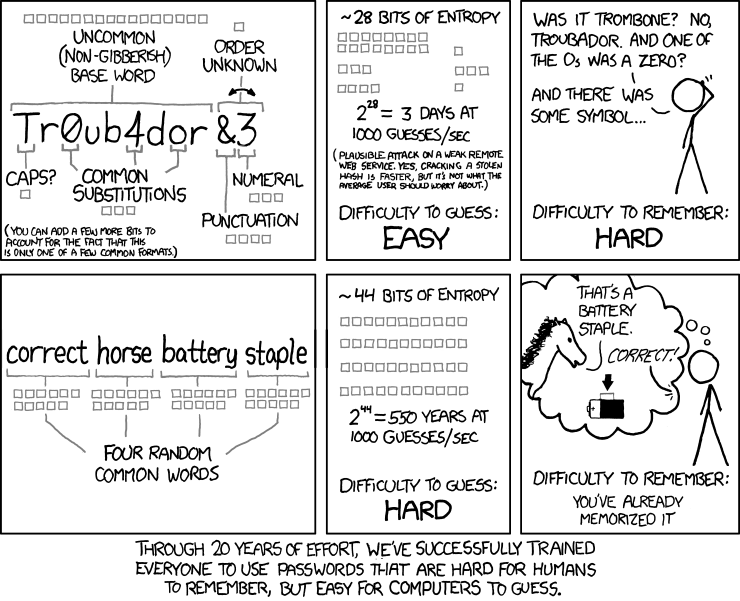

For decades, every password breach has led to the same response, which Einstein would readily have recognised as insanity: ridiculing users for using weak passwords, creating policies that were even more difficult to follow, and calling users “stupid” for devising coping strategies to manage the burden. As Sasse, Brostoff, and Weirich wrote in 2001 in their paper Transforming the ‘Weakest Link’, “…simply blaming users will not lead to more effective security systems”. In his 2009 paper So Long, and No Thanks for the Externalities, Cormac Herley (Microsoft Research) pointed out that it’s often quite rational for users to reject security advice that ignores the indirect costs of the effort required to implement it: “It makes little sense to burden all users with a daily task to spare 0.01% of them a modest annual pain,” he wrote.

When GCHQ introduced the new password guidance, NCSC head Ciaran Martin noted the cognitive impossibility of following older policies, which he compared to trying to memorise a new 600-digit number every month. Part of the basis for Martin’s comments is found in more of Herley’s research. In Password Portfolios and the Finite-Effort User, Herley, Dinei Florencio, and Paul C. van Oorschot found that the cognitive load of managing 100 passwords while following the standard advice to use a unique random string for every password is equivalent to memorising 1,361 places of pi or the ordering of 17 packs of cards – a cognitive impossibility. “No one does this”, Herley said in presenting his research at a RISCS meeting in 2014.

The first of the three questions we started with may be the easiest to answer. Sasse’s research has found that in numerous organisations each staff member may spend as much as 30 minutes a day on entering, creating, and recovering passwords, all of it lost productivity. The US company Imprivata claims its system can save clinicians up to 45 minutes per day just in authentication; in that use case, the wasted time represents not just lost profit but potentially lost lives.

Add the cost of disruption. In a 2014 NIST diary study, Sasse, with Michelle Steves, Dana Chisnell, Kat Krol, Mary Theofanos, and Hannah Wald, found that up to 40% of the time leading up to the “friction point” – that is, the interruption for authentication – is spent redoing the primary task before users can find their place and resume work. The study’s participants recorded on average 23 authentication events over the 24-hour period covered by the study, and in interviews they indicated their frustration with the number, frequency, and cognitive load of these tasks, which the study’s authors dubbed “authentication fatigue”. Dana Chisnell has summarised this study in a video clip.

The NIST study identified a more subtle, hidden opportunity cost of this disruption: staff reorganise their primary tasks to minimise exposure to authentication, typically by batching the tasks that require it. This is a similar strategy to deciding to confine dealing with phone calls to certain times of day, and it has similar consequences. While it optimises that particular staff member’s time, it delays any dependent business process that is designed in the expectation of a continuous flow from primary tasks. Batching delays result not only in extra costs, but may lose customers, since slow responses may cause them to go elsewhere. In addition, staff reported not pursuing ideas for improvement or innovation because they couldn’t face the necessary discussions with security staff.

Unworkable security induces staff to circumvent it and make errors – which in turn lead to breaches, which have their own financial and reputational costs. Less obvious is the cost of lost staff goodwill for organisations that rely on free overtime – such as US government departments and agencies. The NIST study showed that this goodwill is dropping: staff log in less frequently from home, and some had even returned their agency-approved laptops and were refusing to log in from home or while travelling.

It could all have been so different as the web grew up over the last 20 years or so, because the problems and costs of password policies are not new or newly discovered. Sasse’s original 1999 research study was not requested by security administrators but by BT’s accountants, who balked when the help desk costs of password problems were tripling every year with no end in sight. Yet security people have continued to insist that users must adapt to their requirements instead of the other way around, even when the basis for their ideas is shown to be long out of date. For example, in a 2006 blog posting Purdue University professor Gene Spafford explained that the “best practice” (which he calls “infosec folk wisdom”) of regular password changes came from non-networked military mainframes in the 1970s – a far cry from today’s conditions.

Herley lists numerous other security technologies that are as much of a plague as old-style password practices: certificate error warnings, all of which are false positives; security warnings generally; and ambiguous and non-actionable advice, such as advising users not to click on “suspicious” links or attachments or “never” reusing passwords across accounts.

All of these are either not actionable, or just too difficult to put into practice, and the struggle to eliminate them has yet to bear fruit. Must this same story continue for another 20 years?

This article also appears on the Research Institute in Science of Cyber Security (RISCS) blog.

Why aren’t you mentioning password managers/vaults?

Our own research (the NIST study cited) found they are widely used in organisations, and the NCSC guidance we cite says that in most current contexts, companies should allow them if staff cannot cope with the number of passwords they have. There is also a more recent blogpost from the NCSC we should have added https://www.ncsc.gov.uk/blog-post/what-does-ncsc-think-password-managers

Really liked your Article, I think your very spot-on with your assessment. Keep up the good work!

I completely agree with the article. Often, we ‘train’ users to be their own worst enemy and write down their randomized passwords; thus defeating the security altogether. I’m also not a fan of bio-metric authentication as this information is merely stored as ones & zeros and once stolen (and it will be stolen) that authentication is now useless. I can’t change my fingerprint or iris once compromised. I was waiting for the article to address the ultimate issue, a better authentication option. Based on current conditions, my best recommendation to my clients is to use business class password manager. I even suggest it as an employee benefit. Your thoughts?

Here is what I teach for easy and strong passwords:

One Password to Rule Them All by Alex Wawro, PCWorld, updated by Steven Lentz

The first step in creating a strong password is to create a memorable passphrase (avoid first /last name, birthday, pet’s name, street name, username, school) at least 8-10 characters in length. Next mix the characters up with special characters and numbers. In this example we will use the passphrase I love dogs. Next is to mix the passphrase with special characters and numbers to form a single string passphrase: !~7(v#D(gc, (less than 1 day to hack). Not very effective.

Steve’s Updated Version: Now that we have our base passphrase we need to add a KEY & NUMBERS. Everything we access; systems, site and or URL has a name. Let’s use Chase, LinkedIn and Palo Alto as our sites to access. For the key let’s choose the first, fourth and last letter (to make it 12 or more) of the name of each site and capitalize the first letter and insert in the middle of the passphrase. So for Chase our new strong passphrase: 37!~7(v#CseD(gc, (12 centuries to hack). LinkedIn: 37!~7(v#LknD(gc (3996 centuries to hack) and Palo Alto: 37!~7(v#PloD(gc (66 centuries to hack) . The total password length suggestion is 12 minimum: passphrase + key = 12 or more, preferably 15 or more if allowed.

You can come up with a simple naming pattern as a mnemonic device that will help generate a unique password that’s easy for you to remember but nearly impossible for hackers to figure out. No password is perfect, but knowing your own unique passphrase, number and key will go a long way toward keeping your online privacy and accounts intact.