Contactless card payments are fast and convenient, but convenience comes at a price: they are vulnerable to fraud. Some of these vulnerabilities are unique to contactless payment cards, and others are shared with the Chip and PIN cards – those that must be plugged into a card reader – upon which they’re based. Both are vulnerable to what’s called a relay attack. The risk for contactless cards, however, is far higher because no PIN number is required to complete the transaction. Consequently, the card payments industry has been working on ways to solve this problem.

The relay attack is also known as the “chess grandmaster attack”, by analogy to the ruse in which someone who doesn’t know how to play chess can beat an expert: the player simultaneously challenges two grandmasters to an online game of chess, and uses the moves chosen by the first grandmaster in the game against the second grandmaster, and vice versa. By relaying the opponents’ moves between the games, the player appears to be a formidable opponent to both grandmasters, and will win (or at least force a draw) in one match.

Similarly, in a relay attack the fraudster’s fake card doesn’t know how to respond properly to the payment terminal because, unlike a genuine card, it doesn’t contain the cryptographic key known only to the card and the bank that verifies the card is genuine. But like the fake chess grandmaster, the fraudster can relay the communication of the genuine card in place of the fake card.

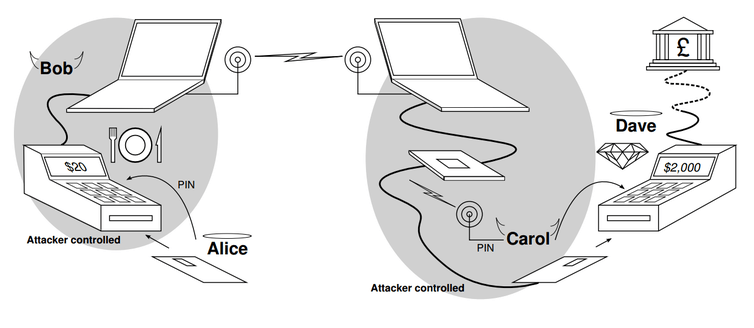

For example, the victim’s card (Alice, in the diagram below) would be in a fake or hacked card payment terminal (Bob) and the criminal would use the fake card (Carol) to attempt a purchase in a genuine terminal (Dave). The bank would challenge the fake card to prove its identity, this challenge is then relayed to the genuine card in the hacked terminal, and the genuine card’s response is relayed back on behalf of the fake card to the bank for verification. The end result is that the terminal used for the real purchase sees the fake card as genuine, and the victim later finds an unexpected and expensive purchase on their statement.

Demonstrating the grandmaster attack

I first demonstrated that this vulnerability was real with my colleague Saar Drimer at Cambridge, showing on television how the attack could work in Britain in 2007 and in the Netherlands in 2009.

In our scenario, the victim put their card in a fake terminal thinking they were buying a coffee when in fact their card details were relayed by a radio link to another shop, where the criminal used a fake card to buy something far more expensive. The fake terminal showed the victim only the price of a cup of coffee, but when the bank statement arrives later the victim has an unpleasant surprise.

At the time, the banking industry agreed that the vulnerability was real, but argued that as it was difficult to carry out in practice it was not a serious risk. It’s true that, to avoid suspicion, the fraudulent purchase must take place within a few tens of seconds of the victim putting their card into the fake terminal. But this restriction only applies to the Chip and PIN contact cards available at the time. The same vulnerability applies to today’s contactless cards, only now the fraudster need only be physically near the victim at the time – contactless cards can communicate at a distance, even while the card is in the victim’s pocket or bag.

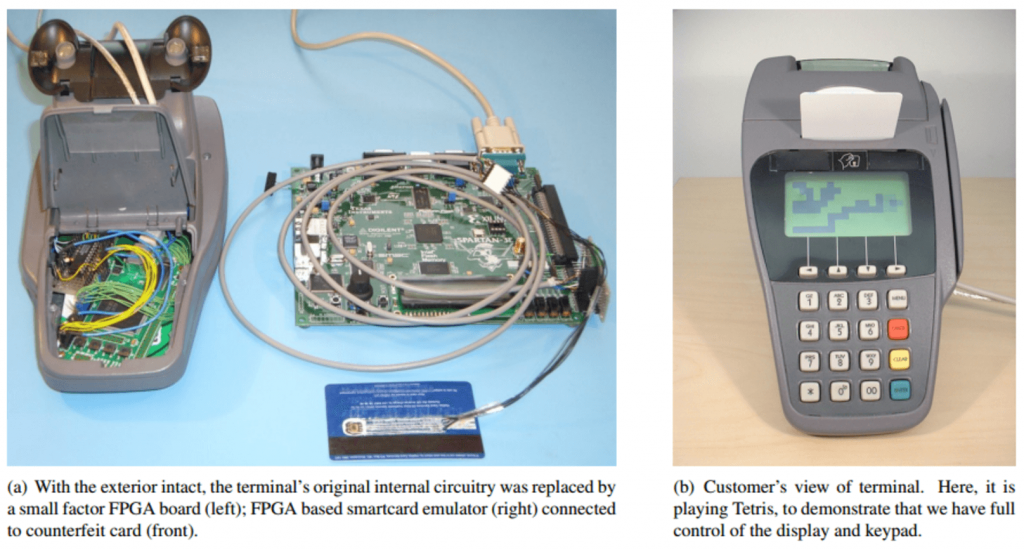

While we had to build hardware ourselves (from off-the-shelf components) to demonstrate the relay attack, today it can be carried out with any modern smartphone equipped with near-field communication chips, which can read or imitate contactless cards. All a criminal needs is two cheap smartphones and some software – which could be sold on the black market, if it is not already available. This change is likely the reason why, years after our demonstration, the industry has developed a defence against the relay attack, but only for contactless cards.

Closing the loophole

The industry’s defence is based on a design that Saar and I developed at the same time that we demonstrated the vulnerability, called distance bounding. When the terminal challenges the card to prove its identity, it measures how long the card takes to respond. During a genuine transaction there should be very little delay, but a fake card will take longer to respond because it is relaying the response of the genuine card, located much further away. The terminal will notice this delay, and cancel the transaction.

We set the maximum delay to 20 nanoseconds – the time it takes a radio signal to travel six metres; this would guarantee the genuine card is no further away than this from the terminal. However, the contactless card designers made some compromises in order to be compatible with the hundreds of thousands of terminals already in use, which allows far less precise timing. The new, updated card specification sets the maximum delay the terminal allows at two milliseconds: that’s two million nanoseconds, during which a radio signal could travel 600 kilometres.

The reason that the timing constraints of the new contactless card standard are much less precise than our prototype is that the new contactless cards’ distance bounding exchange uses the same (relatively slow) communication protocol as the rest of the transaction. In our design, the distance bounding exchange uses a special high-speed mode. Also, the new contactless cards send a single 32-bit challenge and expect a 32-bit response, whereas in our prototype there is a repeated single-bit challenge and single-bit response (based on a protocol by Hancke and Kuhn). For both of these reasons, in our prototype, compared to the new contactless cards, each challenge-response exchange is far more rapid and hence the timing can be much more precise.

Clearly this doesn’t offer the same guarantees as our design, but it would still represent a substantial obstacle to criminals. While it’s enough time for the radio signal to travel far, it’s still a very short window for the software to process the transaction. When we demonstrated the relay attack it regularly introduced delays of hundreds or even thousands of milliseconds. A relay attack against contactless cards using off-the-shelf components would be similar.

It will be years before the new secure cards reach customers, and even then only some: there is only one Chip and PIN specification, but there are seven specifications for contactless cards, and only the MasterCard variant includes this defence. It’s not perfect, but it makes pragmatic compromises that should prevent smartphones being used by fraudsters as tools for the relay attack. The sort of custom-designed hardware that could still defeat this protection would require expertise and expense to build – and the banks will hope that they can stay ahead of the criminals until the arrival of whatever replaces contactless cards in the future.

An edited version of this article was originally published on The Conversation, written by Steven J. Murdoch, UCL.![]()

Hey Steven, just wanted to let you know that we wrote an Android app for NFC relay attacks that’ll run on a modern smartphone (e.g. Nexus 5) and will also fake the UID of the card, and we made it open source. See https://github.com/nfcgate/nfcgate for details. Maybe it’ll be helpful for you or someone else reading the article.

Also, I’m glad to see that this hole is being closed now, albeit slowly. Some systems we tested are vulnerable and will not be getting fixes :(.

@Max,

Thanks for your comment. It is good to confirm that indeed the software needed is out there.

Did you measure the delay introduced by your software? I would be curious to know how much this is in reality.

We did a brief measurement, and ended up with 65 +-38 ms of delay in a local WiFi (See the extended abstract and poster linked in the GitHub Readme). That is mostly due to the fact that we have a client-server infrastructure (Reader Android 1 Server Android 2 Card), which is not very optimized. You could probably lower that latency with direct connections and more efficient code, but obviously not below practical distance bounding limits – it’s a proof of concept and not designed to bypass distance bounding.

There is also a second mitigation strategy banks and shops use – the contactless payment is restricted to something like 20 EUR and you can do only 3 or so in a row. After that the terminal will refuse the transaction and demand a normal payment using chip & pin instead.

So while this doesn’t prevent the attack, it significantly limits the possible impact – in this case to max 60 EUR. Still nasty, but nowhere close to the much higher limits when a regular chip & pin transaction is done.

@Jan

Indeed, transaction limits still apply. In the UK this is £30 per transaction (and there can be a request to enter a PIN periodically, but this has never happened to me).

This mitigates the risk, though there is also the possibility that the limits could be bypassed.

Al this is considering that the payment terminal has been opened without activating the tampering detection which can be done an old terminal as on the video but quite impossible on recently PCI certified device.

The devices when opened are erasing the encrypted key which are allowing them to communicate with the bank. they become useless, especially for the demonstration described in this article.

Nowadays the terminals are well secured but I agree that there are multiple skimmer integration attempts , especially on ATMs with fake keyboard or plates, including cameras, all for capturing the PIN and then it is not the responsibility of the cardholder, I think , if the PIN is stolen.. No we have the PIN on Glass coming soon , which will authorized the PIN to be entered on any phone who’s able to read a contactless credit card and process the transaction, I am becoming really concerned .. especially that a Phone is fully accessible anytime to hackers ( a payment terminal is not by the way) ..

The relay attack doesn’t require evading the tamper-resistance measures because the terminal that the victim interacts with never communicates with the bank. The modified terminal is there to trick the customer into presenting their card (and potentially PIN) so only has to look plausible – the electronics inside can be replaced entirely. PCI security standards only requires that tampering be detectable by the bank, not the customer.

For example, here’s a Verifone SC5000 terminal that we’ve been experimenting with. It’s PCI certified but we were easily able to open it and remove the internals. It has a standard display module which we could connect to replacement electronics. With the addition of a NFC antenna and contactless payment sticker, I’m confident customers would use it without hesitation.

The question of customer liability is a different issue. The approach of the UK banks has been that if a PIN is used for a transaction then the customer must have been negligent and hence liable for the fraud. It would be for the customer to show that the PIN was obtained through skimming, which is extremely difficult. We need changes to regulation to reverse this unfair situation.

It will indeed be interesting to see what will happen with the relaxing of PCI standards to allow PIN-on-glass. Provided that there is robust regulation that ensures risks are not systemic and that customers don’t pay the cost of fraud, I would welcome careful experimentation in this area.

Hi Steven,

I notice that Mastercard have taken measures to address this with the “Relay Resistance Protocol” in M/Chip Advance.

Perhaps they read your blog…

Cheers, M.