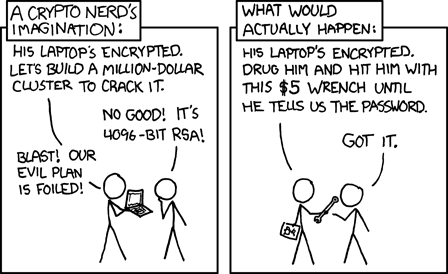

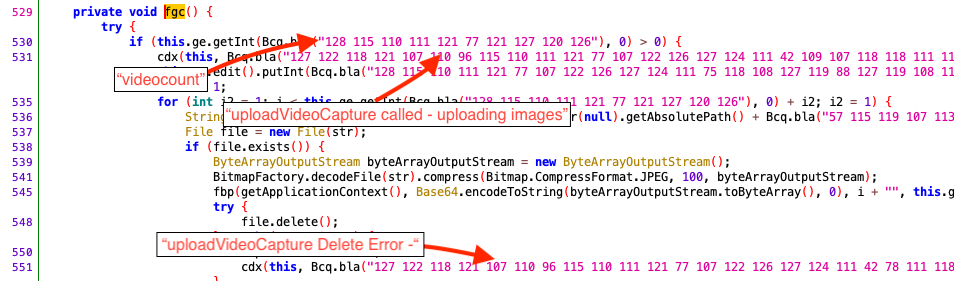

Acropalypse is a vulnerability first identified in the Google Pixel phone screenshot tool, where after cropping an image, the original would be recoverable. Since the part of the image cropped out might contain sensitive information, this was a serious security issue. The problem occurred because the Android API changed behaviour from truncating files by default to leaving existing content in place. Consequently, the beginning of the resulting image file contains the cropped content, but the end of the original file is still present. Image viewers ignore this data and open the file as usual, but with some clever analysis of the compression algorithm used, the original image can (partially) be recovered.

Shortly after the vulnerability was announced, someone noticed that the Windows default screenshot tool, Snip and Sketch, appeared to have the same problem, despite being an entirely unrelated application on a different operating system. I also found a similar problem back in 2004 relating to JPEG thumbnail images. When the same vulnerability keeps re-occurring, it suggests a systemic problem in how we build software, so I set out to understand more about the reasons for the vulnerability existing in Windows Snip and Sketch.

A flawed API

The first problem I found is that the modern Windows API for saving files had a very similar problem to that in Android. Specifically, existing files would not be truncated by default. Arguably the vulnerability was worse because, unlike Android, there is no option to truncate files. The Windows documentation is, at best, unclear on the need to truncate files and what code is needed to achieve the desired result.

This wasn’t always the case. The old Win32 API for saving a file was (roughly) to show a file picker, get the filename the user selected, and then open the file. To open a file, the programmer must specify whether to overwrite the file or not, and example code usually does overwrite the file. However, the new “more secure” Universal Windows Platform (UWP) sandboxes the file picker in a separate process, allowing neat features like capability-based access control. It creates the file if needed and returns a handle which, if the selected file exists, will not overwrite the existing content.

However, from the documentation, a programmer would understandably assume, however, that the file would be empty.

“The file name, extension, and location of this storageFile match those specified by the user, but the file has no content.”

Continue reading The Acropalypse vulnerability in Windows Snip and Sketch, lessons for developer-centered security